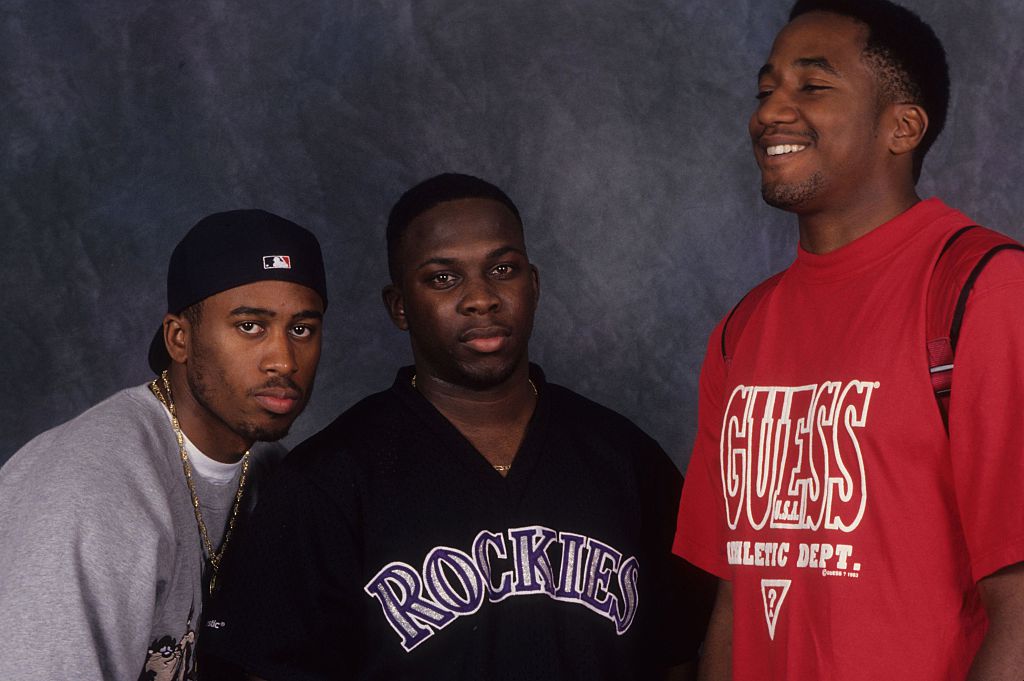

The Making Of ATCQ’s The Low End Theory, Told By People Who Were There

Twenty five years ago today, A Tribe Called Quest released The Low End Theory. The Queens, New York collective had seemingly achieved what so many of their peers aspired to: a record contract, devoted fans, and hits in rotation through a certifiably respected debut. Still, with Q-Tip at the helm, the group fearlessly aspired to further challenge themselves deeply and inwardly. As Hip-Hop peers were channeling Funk, House, and Soul, Tribe embraced the abstract in the free-form spirit of Jazz. In doing so Tip, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and Phife Dawg married lyrics about living, loving, and learning to a new sound steeped in warmth and BASS.

As an act that mimicked a truly indigenous tribe, Quest sought counsel from two understated guests: Skeff Anselm and Bob Power. These two New Yorkers were producers, engineers, and theorists who joined A.T.C.Q. in transforming the studio into a workshop, where for one year, concepts were vetted, skills and roles were refined and redefined, and a masterpiece was constructed out of imagination.

Bob and Skeff retrace the dozen months, 30 tracks, and vast iterations of those 14 songs that make up The Low End Theory for Ambrosia For Heads. In doing so, they discuss the evolution of ATCQ, their approach to music, the ascension of Phife Dawg, what it was like to be in the studio for magical moments like the recording of “Scenario,” and much more. This rich oral history travels back to an album that blew speakers and minds.

Back in the days when I was a teenager…

Skeff Anselm: [Q-Tip] and myself was friends already, prior [to the making of The Low End Theory]. [Our working together] was full circle. It was not like I had to go and get to know Tip; I had known Tip. What happened with Q-Tip, his sister and myself was friends before I knew [him]. I grew up in the Bronx. My best friend, his cousin lived in Queens. So when I used to go with my best friend to Queens, that’s how I met Tip’s sister. She used to hang with his cousin. They were all a little clique out there; they went to high school together. I used to hang out with Tip’s sister; we used to hang out, go on picnics. Then one day I met Tip. That’s how our relationship started. That whole thing with Tip goes back before music. So it was natural when he wanted to get into Rap [he would talk to me] because I was already in the music game; he wasn’t. So it was natural. You’re trying to get into it, so you go to somebody you know that’s in it already.

The Native Tongues have officially been instated

Skeff Anselm: [DJ] Jazzy Jay, who is my mentor, took me underneath his wing. So being around Jazzy got me to learn not just about the engineering and the technical aspect of [music], but more about the culture and learn how to work with different artists per se. ‘Cause I watched him do it. Then, what he learned, he would share with me to the utmost, whether it was the stuff he did with LL [Cool J] or Rick Rubin, [and] Slick Rick. Just being there [as a fly on the wall] or absorbing vocally what he taught me [prepared me]. Being around Jazzy, I got to know [Kool DJ] Red Alert. Being around Red Alert, I got to know [The] Jungle [Brothers]. Red Alert and Mike [Gee] from Jungle are cousins. I knew Red for a very long time before Jungle was formed, before Tribe was formed. It was big brother-little brother type thing. Like Tribe, I’m five years older than those guys. All those guys D.I.T.C., Jungle, and the rest of those cats pretty much was like a family. We was a family. [The Universal] Zulu Nation brought that family together. Jazzy’s studio was the nucleus of bringing all these artists underneath one roof. So it allowed me to really become brothers with all those cats. We all started together. We all grew together. We all argued together. Fought together. [Laughs] It was a family. We hung together. We celebrated together. For us, we did more than just music; it was just [homies]. When we made music, it made the music more natural because everybody was having fun doing it. It wasn’t about the industry, it was just about having fun doing music–that goes for the whole Native Tongues camp on down.

Things done changed

Skeff Anselm: I didn’t see Tip for maybe about two and a half, three years before [People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm] dropped. I think when Instinctive Travels dropped—that whole album, that was it for me. I was a fan out the gate when I heard the album. [There was tremendous growth] from when they first auditioned for Jazzy [Jay], and when I first heard them. Q-Tip was about 15 [or] 14 [when he first auditioned]. It was a few years [earlier]. I think when they dropped that album, Tip was 17 or 18. So it was a few years, and [there] was growth. I was following them as they was going. When the album dropped, I was a fan. [The album] was very unique. The funny thing is how the conversation started with Tip’s voice [in his mid-teens]. His voice was very thin. Fast forward to that album, his voice did not sound like anybody else. That, to me, that uniqueness of his voice, the catchiness of the hooks, and the chemistry of everything, it worked for me. I started as an engineer. Even though I was working in music and working around the circle that I was with of [Grand] Puba, Master Of Ceremonies, and all that, I was still a fan of Hip-Hop in general. But that one album, once I heard it, I was like, “whoa.” It caught me off guard.

One for all and all for one

Skeff Anselm: I was working on One For All with Brand Nubian. We was in the studio working. I don’t know if Tip was visiting somebody in another room at the studio, or he was just coming by or whatever, or walking down the hallway, but he saw me in the studio working [with] Brand Nubian. We just reconnected there. He told me was getting ready to start [A Tribe Called Quest’s sophomore album], so I could come and help him out. And that’s how that came out around. Me and Brand Nubian, we was already a year and a half, two years into a working relationship. I started working with Puba before there was a Brand Nubian. When Puba was working on [Sadat X’s solo album] and Lord Jamar’s solo, we was doing their demos. He was trying to shop them. But nobody was interested; there was no interest in either Jamar’s project or Sadat’s project. So I guess that’s when…it’s funny, I was just watching an interview with Puba talking about how he got his deal. He told Dante [Ross, who wanted to sign him as a soloist], “If you want to sign me, you’ve got to sign these two guys too.” And that’s how that went down. Puba, X, and Jamar was cemented; we had a working relationship. With Q-Tip, like I said, I knew him personally, prior. We just hadn’t run into each other in two or three years [until] the studio. That was the beginning of the beginning. From that time, when I started working on [The Low End Theory], I kinda broke away from Jazzy Jay’s studios thing and started spending most of my time with Tip and them. I mean, practically every day I was in the studio with those guys. They became my family at that time. Even though I was still working with Nubians and stuff—we still had that relationship, day in and day out I was in the studio working on The Low End Theory.

Bob Power: The guys and I got along. They were really fun to be around — 20 years my junior, but a lot of fun to be around. Not knuckleheads, not heavy drug users or drinkers, not necessarily partiers or anything like that, so it was a good match.

Let me flaunt the style. I think that the time’s near

Skeff Anselm: When Tip started sampling a lot of the basslines, on the Jazz records, he was focusing on the bass. He pretty much told Bob Power, “I want the bottom to be as heavy as you can make it.” So every track was following suit. I guess when Bob was mixing, he tried to keep everything within that same range. In fact the only two tracks that wasn’t really, really low was mine. If you listen, I did “Show Business” and I did “Everything Is Fair.” If you listen to mine, it’s not as low as the samples that Tip did on the rest of the album.

Bob Power: Tip and Ali [Shaheed Muhammad] happened to be using a lot of fairly esoteric and Jazz-based stuff in there. What I was doing was just trying to clarify the sonic realization of that—and, again, I worked really hard. If there was a sample that they used that had happened to have an electric piano in it, but there was a whole band in there, but the important part was the electric piano part, I would do everything I could to take the band out of there so you could really hear the clarity of the musical constructions better.

Skeff Anselm: So Tip, when he put his headphones on and is listening to his records, he’s listening for a particular thing—and he found it in the stand-up bass. His drive for the whole album was strictly on the bass. That’s why he brought Ron Carter in to play the bass on [“Verses From The Abstract”] and you’ve got live stand-up bass. That’s self-explanatory on how he came up with the title, The Low End Theory. It’s all about low-end on that album. After we did that album, we went on tour. I was doing sound for them on tour; we did a college tour. When we was doing soundcheck and I was listening in the system, half of those speakers couldn’t even handle that shit, because they wasn’t used to it. [Laughs] We even blew speakers in some spots.

Bob Power: I will say that oftentimes Tip would bring in a record and say, “I wanna sample this bassline,” and it was, you know, something very sort of normal, like a Samba or a Bossa Nova bass line, and I’d think, “Okay, well, he’s gonna put it in the track like . . . ,” and then he’d say, “No, no, no. I want it to go . . . ” You know, something really, completely reconstructed, and it was always a delight for me because I’m an over-trained musician and composer and I’m used to “It is what it is.” When you hear it a certain way, or you realize it a certain way, that’s what the musical phrase is , and Tip would always recombine things in ways where it’s just, “Oh my God, that’s really cool.” He totally ripped it apart and put it back together again, and it doesn’t bear a whole lot of resemblance to the original.

Skeff Anselm: Crafting the sound, Tip pretty much did most of the sampling on the spot. He did a few of them at home. While he was layering, he was layering the different parts and getting the different parts back. He’d ask my opinion about it. I’d give him my two cents. If he liked it, then he’d pass it on to Bob [Power]. Bob would do what he do. Bob would tweak it. Bob was a person who liked to pull out all the latest toys. So there’s stuff Bob did with the [equipment] that gave it that sound. He was mixing it like he was mixing real, actual instruments in front of him. In Bob’s ear, that’s how he was trying to do it—real instruments. I mean, they are all real instruments coming back off of the record, but [they are] samples. You still lose a generation from the original instrument, so you’re trying to bring that sound out from that instrument and have it blend the way it’s supposed to blend. And he did a great job, as you can hear.

Bob Power: The development of Hip-Hop and tracks, and track making and sample usage, has a remarkable and obvious parallel to technology — and as sampling time became expanded, people were able to do more live reconstructions with records. The very early stuff was usually a drum machine and then a DJ cuttin’ back and forth between the same record, almost like a Kanye [West] track, where you hear the same little loop over and over again throughout the song. Early on, in the late ’80s, samplers were used primarily for drum sounds, just because you didn’t have a lot of memory, but occasionally there’d be a little melodic snippet or James Brown screaming, or whatever. Then, by the early ’90s sampling time had expanded to the degree that you could actually put whole musical phrases in there, and you could put a whole bunch of different ones in at the same time, so you could actually hear your creation in real time. Before that, and much of what was done on the first couple of records, we had to actually construct the pieces in the studio and put them on tape track by track — so, until that point, I don’t think the guys were able to really hear their creations other than inside their head, which is remarkable when you think about it.

Skeff Anselm: With Bob, as time started going, when we went from Low End to Midnight [Marauders], we was using less loops and more drum programming. The way I used to do my kicks and snares, I had bright kicks and snares. My snares used to always be poppin’. Pop! When I used to be playing my beats for the guys, Bob would be like, “Damn, Skeff. Wow. It’s bright.” I noticed when he was EQ’ing, he’d EQ close to that bright [area]. He’d get a snare to be poppin’ and tight. I think some of that he took from me. I’m not gonna take credit for all his genius, but i think he took that from me.

Bob Power: Ali’s strength, at that time, [was] most of the beats where the drums kind of really drove the whole song in a very driving way. Not to say that Tip didn’t do that, but that’s what I remember. Ali also was technologically always sort of pushing the front end of things. He was one of the first guys I know to actually bring a Mac [computer] to the studio that he’d been sequencing on, when Tip was still on the [E-mu] SP-12 or [Akai] MPC. That was sort of just how people create the best. It really had nothing to do with like, “Oh, I wanna be cutting edge,” it was like, “Wow, this is a good tool for me.” But both of them really had this, and I’ve said this before, but had a very uncanny ability to hear combinations of things in their head that were pieces of different things that no one had ever really thought about putting them together in that way before. And, because, back then, the sampling time and the technology was so limited–and really it was all about sampling time—a lot of those constructions they had put together in their head, and they still couldn’t realize it in real time until we got to the studio and put it together piece by piece, which I find pretty startling in its imagination and creative imagination.

Check the rhyme, y’all

Skeff Anselm: Even [on songs] I wasn’t producing, I was still there. They would still ask me for my input. Tip would be working on a beat and turn to me, “What you think?” He would respect my input on whatever he was doing. It also went into recording vocals. As time went on, there were times when he was getting frustrated with Phife [Dawg]. He was like, “I can’t work with this guy right now. I can’t work with him! I don’t know. Skeff, see if you can work with him.” Most of the time, for half of the album, I was there with Phife working on his vocals. He’d turn to me for feedback. “It’s cool, leave it. Move on.”

Skeff Anselm, he gets props too

Skeff Anselm: Delivery. Content, pretty much Tip would stay on [Phife] about the content or lyric. “Yo, you can’t say that.” [Laughs] Phife was always pushing the boundary. Phife was always the one, if you listen to the styles and the content of the lyrics, Phife would say stuff that the average person wouldn’t say. Tip was more conservative. Sometimes, Tip would have to pull him back. So I didn’t help him with his content. More so, his delivery and execution. Staying on beat and his flow style. He’d say something, and I’d be like, “Try it again.” Then he’d do it. He’d finish all his vocals. We’d play it back for Tip. Tip would say yes or no, or “just change that part.” That was pretty much my relationship with Phife while he was working on his vocals on Low End Theory. That’s why you hear the shout-out on “Jazz” because I was there everyday. Like I said, if I wasn’t working on a track, I was there.

Phife Did-dawg is in effect

Skeff Anselm: If you hear interviews with Phife in reference to [why he did not have as much of a presence on People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm], you’ll pretty much hear at some point when they started working on Instinctive, he started losing the taste for it. He wasn’t into it much. At some point, he felt he was gonna give up on it. He didn’t want to do it, but something kept it going. I don’t know what that was. Maybe it was his friends—[especially] Tip. Maybe it was his inner-circle, his family, but at one point something just made him go forward. Then on Low End Theory, he started writing more. Jarobi used to be in the sessions. Then I guess he fell out of love with it at the time. That’s why you hear no verses from Jarobi on The Low End. Then, Phife started filling in more of that space. If Jarobi would have stayed around [he would] have had more vocals. I think [Phife’s] evolution came from his peers. When you have cats like Leaders [Of The New School] comin’ through—a lot of cats was comin’ through the studio. Everybody was pushing the boundary or the envelope. Coming to the studio, everybody’d be freestyling, so you feed—everybody’s feeding off of each other. So that’s how you get that growth from him. It’s not just him going in the booth and laying it down, they used to freestyle a lot in the studio. It’s like going into the gym and working out: you do 10 pushups and you see [another] man do 20, you [attempt] 30. [Laughs] Meanwhile, you’re getting stronger as you’re going, ‘cause your peers is pushing you. You’re pushing [back].

Bob Power: Phife’s contribution as an MC, and particularly for hooks or catchphrases, or just the variety he brought to the delivery of the song, became an arrangement element in itself. I can’t really separate him from the flow of the music in general, because his sense of cadence and flow was just very unique and very him. I actually appreciate it a lot more now than I did then, ’cause now I go back and listen and I have some context and he’s very funny. His flow is extremely different from everybody else’s — not just on the records, but a lot of people in general. You know, he’s very much on the beat, which is sort of an old school thing. But his flow is really interesting to listen to just because of his rhythmic ideas, And, it’s very conversational, so you don’t feel like he’s putting anything on. You just feel like he’s this larger than life character, which is what you really want from an artist.

Skeff Anselm: When I first [recorded] Brand Nubian with Tribe [for “Show Business”], we recorded it at Jazzy’s studio. Then, we redid the song ‘cause we didn’t like the direction the song was going. Tip and Chris Lighty…pretty much Chris Lighty didn’t like the direction the song was going. Then, we redid the song and did it in Battery Studios. On the streets of New York, Brand Nubian [was] getting much props [at the time] just holding their own. [Phife could be thinking], “Now, I gotta go on this track with Brand Nubian. I gotta come wid’ it.” So all that interaction with other rappers really allowed him to start developing himself. I think that’s what helped him get better, and better, and better, and better. Also, you’ve got to take into consideration [that] there was a lot of songs recorded that didn’t make the album. During those songs that was recorded, you also had given him time to really sharpen his skills on all these other songs that was not used. It wasn’t like, “Okay, we’re doing 12 songs? [Here are your] 12 songs.” No. They did 20-something or 30 songs. Tip buried them suckas. I think one day he’ll probably release them—for Phife.

A Tribe Called Quest Secretly Recorded An Album That Is About To Be Released

Competition’s good. It brings out the vital parts

Skeff Anselm: [Phife Dawg’s improvement] helped Tip. Because once he saw Phife was growing, it helped him push his game up. Tip’s style was more about concepts, stories, and that’s what gave you the balance in Tribe. ‘Cause if you listen from the first album to “Bonita [Applebum]” and all those other songs, it’s taking you on a journey. Even “I Left My Wallet In El Segundo,” it’s stories. He’s a concept person. That’s why you get that balance. If it was all concept, it gets tired after a while. Once you get the balance of the edge of Phife, it takes you away and brings you back. It’s that Yin-Yang balance between those two guys.

Skeff Anselm: I think [making “Butter” and “Verses From The Abstract” solo songs] was [Q-Tip’s] idea. I think he wanted Phife to shine. Tip recorded two or three songs solo. I remember now. He did like two or three songs solo. Because he did that, Phife was like, “Yo. What’s up?” [Laughs] [Q-Tip said], “This is what’s up. Okay. You’ve got yours. This is you. Do you.” That’s how it ended up being solos for both of them.

Inside, outside come around

Skeff Anselm: I knew [and] they knew that “Scenario” was hot. The thing is with that song, they had about 20 people recording that song until they started ixnaying people out. Chris Lighty rapped on one of the [versions] of the song. [Chuckles] Then, they did the “Scenario (L.O.N.S. Remix).” You had [Posdnuos doing one verse]. There’s a lot of other people that rapped on the song. But they just pulled their parts out and kept the Leaders and Tribe on the finished product. But when we played it back, everybody in the room knew that track was a hit. They were just soft-spoken [about it]. It did what it did; the energy was right. I think Leaders respected [A Tribe Called Quest] so much that they felt it was just a blessing to be in their space, and to share that energy. It was [not about competition]. It was all about love and having fun. Laughing and enjoying the moment.

“Delivering each year an LP filled with street goods“

Skeff Anselm: It took us about a year [to complete the album]. It would’ve been longer, [because] Tip is a perfectionist. Chris Lighty came to us and said the label wants an album. “Gimme what you got, I’m gonna do my meeting.” Tip wanted to keep recording and recording, and keep going and going, and going. [Jive Records] said, “Here’s the release date, and that’s it. Finish mixing it.”

Bob Power is in the house

Bob Power: That was a time of huge growth for me as an engineer, ’cause I had had a sort of 20-year viable career before that as a musician and a TV composer. So, it was a time of great growth for me early on in my engineering career, and, obviously, for the guys, it was a time of great growth for them in terms of their record making skills, so it worked really well, hand in hand. We were all sort of fascinated by the same things. The nice thing is, the guys gave me a lot of room to do my thing, and I do things very differently now, but towards the same end, because I kind of know what I’m doing a lot better now that I did that. But still, they gave me a lot of room. They knew that I really put an incredible amount of energy and focus into stuff, so if I needed some time to realize something they would always give me that time — and then stand over me and say, “More kick, more snare, more kick, more snare,” which is funny.

A perfectionist at work, perking up the art

Skeff Anselm: We sequenced the album, which I give Tip crazy props for, ‘cause…he’s a genius. I’ll give it to him. To sit there and watch him sequence the album, and watch him [piece it together]. I was there for the whole sequencing of the album. I think with this album, he went by the topics. So whatever the topic of that one song was, he followed it. That was his method. Whatever he was talking about in one song, it almost had to gel going into the next song. Because most of the tracks was all the same tempo. The fastest tracks on that whole album were “Show Business” and “What?” Everything else was close to each other in the same tempo. Tempo-wise, of course it’s gonna flow naturally. It was like telling a story, going somewhere. After we finished sequencing the whole album, I got a cassette of it. I went home and played the cassette and let it play from beginning to end. It felt like, “This is good. This is really good.” I remember I played it for one of my best friends. He was like, “Yo Skeff, this album is official.”

Check it out and give me my ‘spect

Skeff Anselm: To tell you the truth, maybe about a year after the album dropped [is when I realized its impact]. About a year. The feedback [let me know]. You know what did it? When we went on tour. The college tour was De La [Soul], Tribe, and we would have other artists come in and out from around the country. When we did the tour and saw the reaction of the students—at the colleges and a couple theaters, just to see how everybody was reciting the lyrics. The album was out for four months. Then we did the tour, and everybody knew the album verbatim. They knew every frickin’ word in four months. That means everybody was listening to the album day in and day out, back and forth and forth and back and back and forth—to the point that they could come to a show and recite verse for verse, all the songs that they did for that album. And that’s what blew me away. That’s when I knew that this shit was something. It humbled me. On top of that, the most humbling thing was my son was born six days after the album. He was born on the 30th, September 30th. It was a true blessing.

Bob Power: I think that record, that era of records and Hip-Hop in general really changed the way everybody hears low frequency and its place on records. You know, just ’cause of my conditioning through that period, even when I mix Rock records now, they tend to be a little bit bigger and fuller on the bottom than other people might do. But I think that era and that record, by nature of the name alone, if not the content of it, really changed the way people hear low frequency.

A Tribe Called Quest’s Low End Theory Was Certified Platinum 20 Years Ago Today

Skeff Anselm: The thing is, when we was doing it, we didn’t know that it was gonna be what it is today. We didn’t, for real. It was just having fun, working on an album—jumping on a couch and doing what young people do, have fun.

Bob Power: The great pieces of art that have [been] made by more than one person, [were] usually a confluence of time and place and people that can never be recreated again, because those three things will never come together in the same way.

Find Amanda Mester on Twitter.