Explaining Kendrick Lamar’s Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers Albums

More than any other artist in Hip-Hop, and perhaps in all of music, Kendrick Lamar expresses himself through albums. Over the years, these albums have shown themselves to be dense bodies of work, filled with cryptic references and hidden meanings. Entire college courses and podcast series have been devoted to decoding Kendrick Lamar LPs. Ambrosia For Heads was among the first to report that Kendrick’s DAMN was actually 2 albums in one, taking on different meanings depending on whether the album was played in forward or reverse order. Now, in listening to the newly-released Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, it is clear that Kendrick has done it again.

Here is our analysis of the many nuances packed into this complex artistic work.

Although the album was released on May 13, the rollout actually started with the album’s announcement in August 2021. In a statement posted to his website, oklama.com, Kendrick wrote, “The morning rides keep me on a hill of silence. I go months without a phone. Love, loss, and grief have disturbed my comfort zone, but the glimmers of God speak through my music and family.” Signed “Oklama,” which we now know from Dissect, likely means “my people,” in the language of the Choctaw indigenous people, the moniker is often used when a poet or prophet is addressing God’s people on God’s behalf.

The Rumors Were Right. Kendrick Lamar DID Release 2 New Albums.

Now that the album has been released, we know just how intentional Kendrick’s language was in his release letter. The references to hills of silence, his isolation from technology, and the love, loss and grief he says he experienced would all be discussed on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers (but more on that later). The use of the name “Oklama” also started a frenzy of speculation about its meaning, for months. It began to come more into focus with the release of ‘The Heart, Pt. 5,” the single Kendrick dropped on Mother’s Day. Kendrick’s choice to release the song and video on a holiday with no warning seemed strange, but, as we would learn from the album artwork he released a few days later, Kendrick is now the father of not one but two children–a daughter and a son.

View this post on Instagram

Whitney, his fiancee and the mother of his children, is featured prominently on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, and his own mother is frequently referenced, so the timing of the release of “The Heart, Pt. 5” on Mother’s Day was surely symbolic.

The first thing we see in the video for “The Heart, Pt. 5” is a note that says, “I am. All of us.” This is consistent with Dissect‘s interpretation of the meaning of Oklama. Kendrick’s first words are, “As I get a little older, I realize life is perspective. And, my perspective may differ from yours. I want to say thank you to everyone that’s been down with me; all my fans, all my beautiful fans–anyone who’s ever gave me a listen (the importance of this will come up on the album too)–all my people.” “My people“…those are the last words Kendrick utters before tearing into a ferocious rhyme. Oklama.

While much has been made about the deep fakes that follow in the video, a key detail might have been missed from the very beginning; one that again only comes into focus after the release of the album. For the entire opening monologue and opening verse, Kendrick is looking off to the side. But why? Everything Kendrick does in his art is intentional, so there must be some meaning behind this. Now, fast forward to the last song on the second set of 9 songs on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. The title of that song is “Mirror.” For years, Kendrick has mentioned that his morning ritual was to get up and look at himself in the mirror, often for as long as 30 minutes. He does this not out of vanity, but to study himself, dissect himself, and take note of the man he is and perhaps who he wants to be.

Now, imagine that what Kendrick is doing as he looks off to the side in the video for “The Heart, Pt. 5” is looking in the mirror, and listen to the words he says in that first verse, punctuated by “‘Cause I want you to want me too.” It would not be the first time a Kendrick rap conveyed a conversation he had with himself in the mirror. He has another similarly intense dialogue with himself on “u,” from 2015’s To Pimp A Butterfly, rapping, “I know your secrets. Don’t let me tell them to the world about that sh*t you thinkin.’ I’m f*cked up, but I’m not as f*cked up as you. You just can’t get right, I think your heart made of bullet proof. Shoulda killed yo ass a long time ago. You shoulda filled that black revolver blast a long time ago. And if those mirrors could talk it would say ‘you gotta go.’”

Kendrick Lamar Breaks Down To Pimp A Butterfly’s Cover Art and Its Significance (Video)

In the transition from verse 1 to verse 2, Kendrick turns his gaze from himself to the audience, saying, “Look what I done for you.” The second verse plays like a continuation of the conversation he began on To Pimp A Butterfly’s “Mortal Man,” a song that takes an in-depth look at people’s fickle relationship with those they idolize. Kendrick asks on the song, “when sh*t hits the fan, is you still a fan,” and questions whether he would have the latitude to make mistakes without being persecuted.

In verse 2 of “The Heart, Pt. 5,” Kendrick faces his fans and morphs into OJ Simpson, Kanye West, Jussie Smollett, and Will Smith, all people once-beloved who have been canceled (to varying degrees) over the years. Cancel culture will also be a recurring theme on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. In an extended portion during the second verse, Kendrick’s face reappears, and he once again looks to the side–in the mirror–and raps “Dehumanize, insensitive, scrutinize the way we live for you and I,” seemingly another aside with himself.

Verse 3 of the song finds Kendrick rapping from the perspective of Nipsey Hussle, in the afterlife. He raps about staring down the barrel of a gun, encourages his fans to make investments (a staple of Nipsey’s economic teachings), and specifically tells his brother, Sam, that he will be watching over him. The visuals are punctuated with an appearance by the late, great Kobe Bryant. Perhaps he and Nipsey are among the losses Kendrick referenced in his statement from August.

The last words that Kendrick says on the song are “I want you.” It’s unclear to whom or what he is referring, but throughout the song, he has made reference to “the culture.” Although most of those references have been derogatory, like Common, Nas, and others who have lamented the state of Hip-Hop–the culture–it is possible that Kendrick’s final sentiment is that, despite how the culture has been twisted and distorted to lead to death and destruction, he does still want it. He also wants to be loved by the hood again.

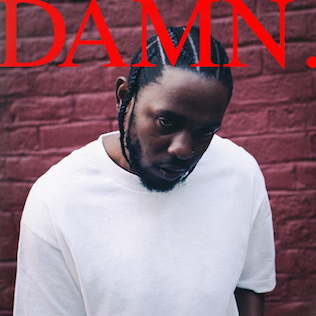

As we will see when we examine the album, “The Heart, Pt. 5” sets up what to expect from Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. It is also a bridge between that album and DAMN. Sonically, it is much closer to DAMN, with its soulful, immediately accessible replaying of a 1970s Marvin Gaye song. Visually, it also references both albums. The background behind Kendrick in the video for “The Heart” is nearly identical in color to the wall in front of which he stands on the cover of DAMN. Also, Kendrick is wearing a plain white T-shirt on the cover of DAMN, in the video (plus a bandana in tribute to Nipsey Hussle), and on the cover for Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. And, with that, we are set up for Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers.

As we now know, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers is actually a double album, featuring 2 different volumes with 9 songs each. The first order of business is figuring out in which order to listen to Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. As Ambrosia For Heads revealed with DAMN, Kendricks’s albums are often meant to be consumed in orders that are different from how they are presented. DAMN, for example, was meant to be played in forward and reverse order, with each direction providing a different story arc and ending to Kendrick’s journey on the album(s).

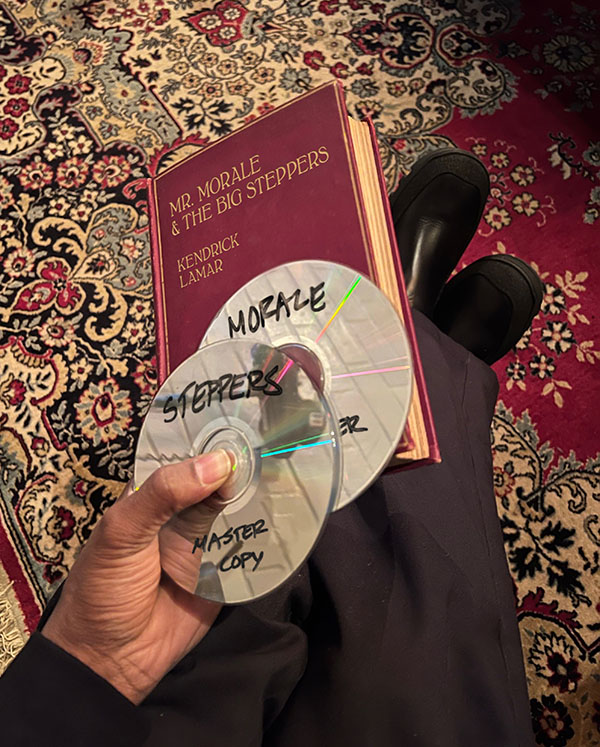

A few weeks after announcing the title of Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers in April 2022, Kendrick released a cryptic image of him holding 2 CDs in his hands, with one bearing the title “Steppers” and the other titled as “Morale.” The CDs were held with a book titled “Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers,” suggesting that the albums were volumes of the same book.

The image immediately fueled rumors that Kendrick’s new work would be a double album. Sure enough, when Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers appeared on streaming services, there were 18 songs, with 2 batches titled 1-9. However, when looking at the tracklist and listening to the songs, the first grouping of 9 has multiple references to steppers, including #3, “Worldwide Steppers.” Similarly, the 2nd grouping of 9 songs has a number of references to morale, including the on the nose 7th track, titled “Mr. Morale.” Further, when the image of the 2 CDs and book is revisited, we see that Steppers is first and Morale is second.

Upon listening, the albums could easily be in the order in which they are intended to be consumed. The first words we hear on “United In Grief,” song 1 on The Big Steppers, are “I hope you find some peace of mind in this lifetime,” with a woman chiming in with “Tell them. Tell them the truth.” That’s followed by “I hope you find some paradise,” with more exhortations to tell the truth. Kendrick’s first words are in line with the command. He says, “I’ve been going through something. 1,855 days. I’ve been going through something. Be afraid.” 1,855 days is 5 years and 30 days ago, which is April 14, 2017, the day DAMN was released. The implication is that Kendrick is about to catch us up on everything that has happened since he last spoke to us through his music. In the song, Kendrick raps about the many luxuries in which he’s indulged over the last few years–a G-Wagon Mercedes, a Porsche, jewelry, 2 mansions–and yet he’s still grieving. He once again mentions Chad Keaton, a young friend who was like a little brother, who was killed 9 years ago. Kendrick rapped about him on “u” and on other songs. While Kendrick makes it seem like he’s been using materialism as a salve, he also suggests he’s doing it for “the culture,” saying “the way you front, it was all for Rap.” This is a sentiment he teed up in “The Heart, Pt. 5,” with the JAY-Z-inspired line: “I said I do this for my culture, to let y’all know what a ni**a look like in a bulletproof Rover.”

When the project is played in the order it appears on streaming services, the last song is “Mirror.” As we’ve discussed, Kendrick may be looking in a mirror during “The Heart, Pt. 5” video. Kendrick revisits themes from “The Heart” in “Mirror.” On “Mirror,” he says, “Lately, I redirected my point of view,” which is consistent with his opening in “The Heart,” where he says he’s realized life is perspective. Also, “Mirror” seems to be a metaphor for Hip-Hop and the pressures Kendrick has felt under its weight, as its involuntary savior. He raps of his subject: “you won’t grow waitin’ on me” and that he’s no longer willing to sacrifice himself for it. “Maybe it’s time to break it off. Run away from the culture to follow my heart,” and “Sorry I didn’t save the world, my friend. I was too busy buildin’ mine again.” He closes with “I choose me, I’m sorry,” which seems to be a different conclusion about the culture than the one he reached at the end of “The Heart, Pt. 5” (“I want you”).

Both “United In Grief” and “Mirror,” seem like fitting beginnings and ends, respectively, for the album. However, things get interesting when the order is flipped. If “Mr. Morale” is, in fact, the disc that should be listened to first, “Count Me Out” becomes the album opener. That song begins with Sam Dew singing, “We may not know which way to go, on this dark road. All of these h*es make it difficult.” In between these 2 statements, spiritual adviser and philosopher Eckhart Tolle interjects with “Mr. Duckworth.” Tolle is featured and referenced a number of times on the album. The beginning of “Count Me Out” is eerily reminiscent to that of DAMN, which opens with Bekon asking listeners, “Is it wickedness. Is it weakness. You decide. Are we going to live or die?” That intro on the song “BLOOD” set the stage for listeners to decide in which order they wanted to play DAMN, and consequently, whether they wanted the story to be one of destiny and damnation or free will and breaking generational curses (more on that later). Also, Tolle’s saying “Mr. Duckworth” potentially picks up where DAMN left off, with the song “DUCKWORTH,” when played in its original order, which ends with Kendrick rapping about the curse of his family beginning to be reversed.

Kendrick Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d. city Turns 5. It’s Past Time To Call It A Classic (Video)

When played in this new order, the last song on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers then becomes the Ghostface Killah and Summer Walker-featuring “Purple Hearts.” That song ends with Kendrick saying, “if God be the source, then I am the plug talkin.’” Kendrick is thus saying he is God’s messenger, which brings us back to Oklama. Thus, starting with “United In Grief” ends with Kendrick doing a 180 from “The Heart, Pt. 5” and deciding to move on from the culture on “Mirror.” Starting with “Count Me Out,” concludes our musical journey with Kendrick delivering his message from God. “We may not know which way to go on this dark road…”

Before diving too deeply into Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, let’s quickly revisit the core themes of Kendrick’s previous albums. good kid, m.A.A.d city was Kendrick’s coming of age story. To Pimp A Butterfly dealt with the guilt he was facing, having become famous and left many of his friends and family behind in Compton. DAMN found Kendrick wrestling with the notion of free will vs. destiny, and whether we all were locked into the chain of our DNA or able to take actions that allowed us to break those generational bonds. Regardless of which listening path we choose, at its core, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers is about Kendrick reflecting on himself and how he relates to family.

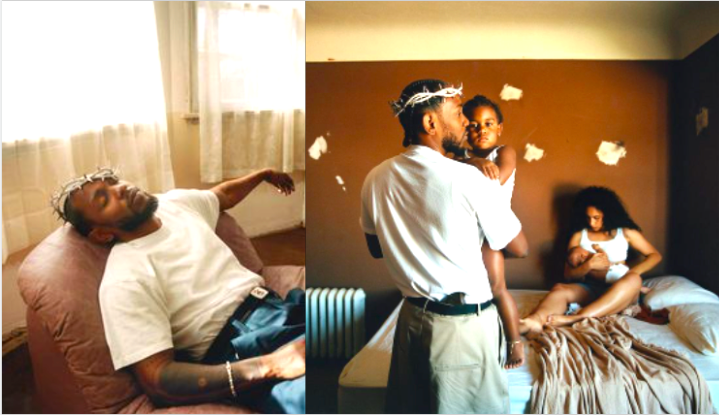

In the 1,855 days since DAMN, Kendrick Lamar’s family has radically changed. Where the family portrayed in good kid, m.A.A.d. city prominently featured his mother and father, Kendrick’s immediate family now consists of his fiancee and longtime partner, Whitney Alford, his 2-year old daughter who’s name has not been revealed (until possibly on “Mr. Morale”—and more on that later), and his recently born son, Enoch. Kendrick places the theme of family front and center with the Renell Medrano-shot photo he uses as his album artwork. The photo features him standing and holding his daughter. Whitney is sitting on a bed holding their son, perhaps preparing to breastfeed. Everything about the image portrays modest living. There is no artwork on the walls. In fact, the paint has several very visible chips. There is no furniture, aside from the bed, which has no headboard and a very plain blanket. All we can see on Whitney and their daughter is white tank tops. Kendrick is simply wearing a white T-shirt and khakis held up with a black belt, which conveniently serves also to hold a gun he has tucked away. Kendrick is also wearing a crown of thorns, a theme that surfaces many times on the album. There is not a single electronic device to be found.

While it’s quite doubtful that this is his actual bedroom, the photo seems to be a clear statement about Kendrick’s chosen lifestyle in this modern age. It is also the visual manifestation of the life Kendrick told us he was living with his testament back in August: “I go months without a phone. Love, loss, and grief have disturbed my comfort zone, but the glimmers of God speak through my music and family.”

On an image posted by Medrano on May 13, the release date of Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, we see Kendrick sitting on a chair in what appears to be another room. This room is similarly sparse, also showing no electronics, artwork, or other furniture. Kendrick has swapped jeans for his khakis, and it is unclear if the gun is still tucked into his belt. However, there is now a shotgun very prominently placed in the corner of the room by the window. Both this image and the first one evoke memories of the famous photo of Malcolm X standing in his home, peering out the window while holding a shotgun. The photo first appeared in the September 1964 issue of Ebony magazine, 5 months before Malcolm’s death. Over time, it became associated with the phrase “by any means necessary,” which became a mantra for Black empowerment. In 1988, KRS-One replicated the photo for the album cover of Boogie Down Productions’ By All Means Necessary. If taken together, these 2 images of Kendrick are quite likely the individual covers for the Mr. Morale and The Big Steppers albums.

View this post on Instagram

Both Kendrick and Medrano captioned the image of him and his family as Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. On the second image of Kendrick by himself, Medrano uses the caption “The Big Stepper.” However, it’s important to note that, as of May 14, Kendrick has yet to post the pic. Thus, it’s quite possible that the second image is that of Mr. Morale, and the image with Kendrick and his family is actually The Big Steppers. This is supported when we turn back to the way the music is presented on the album.

In the second batch of 9 songs (where song #7 is “Mr. Morale”) song #2 is “Crown.” On that song, Kendrick laments the pressure that comes with being anointed as Hip-Hop’s proverbial savior: “Heavy is the head that chose to wear the crown, To whom is given much is required now.” These words are consistent with the story the image of Kendrick sprawled on the chair tells. So, it seems the second batch of 9 songs is Mr. Morale, and we now have artwork for that body of work.

When we step back and consider the two batches of 9 songs and their corresponding photos, it suggests that the Mr. Morale section is more about Kendrick looking in the mirror at himself, and examining his ongoing struggles with fame, personal growth and the weight of being Hip-Hop’s savior, a title he never sought. The Big Steppers section gives us more insight into how Kendrick has been adjusting to his new family, including his dynamic with Whitney Alford. Again, Kendrick seeded these thoughts in his August statement: “The morning rides keep me on a hill of silence. I go months without a phone (Mr. Morale),” and “Love, loss, and grief have disturbed my comfort zone, but the glimmers of God speak through my music and family (The Big Steppers).” And, as we saw, these themes are all over “The Heart, Pt. 5.”

While there is certainly overlap in subject matter between the two albums–after all, Kendrick is at the center of both, and like him standing in the mirror, they are reflections of each other–these basic frameworks seem to hold up, as we examine the album.

Let’s take a look:

Mr. Morale

The album is filled with introspective themes. Sonically, the intimacy of the lyrics is heightened by a minimal use of drums. Songs like “Crown” have no drums at all, while every song until “Auntie Diaries” starts with no drums. Nearly every song is outwardly dark, with undertones of hope.

“Count Me Out,” the first song on Mr. Morale, is Kendrick providing a recitation of his many struggles–infidelity, fame, shutting down emotionally and mentally, dishonesty, and more. His relationship with the mirror surfaces, too, with him saying, “Look myself in the mirror. Amityville, I ain’t seen nothin’ scarier,” a clever nod to The Amityville Horror story from the ’70s, which was made into a book and cult classic film. He also acknowledges that he can be his own worst enemy, rapping, “Ain’t nobody but the mirror lookin’ for the fall off.” By the end of the song, it is clear Kendrick is fighting these demons, and he wonders if anyone else has similar struggles.

At its core, “Crown” is about the expectations and responsibilities Kendrick carries because of his fame and wealth, and the conflict that comes with that. He’s expected to give money to people and, even though he does, the minute he says no, all the other times are forgotten. Although he’s extremely busy, he gives his time to loved ones–sometimes–but makes sure they know he’s made the sacrifice. He also talks about how fickle love can be from the public, and goes out of his way to say keeping his music in rotation is a sign of love for him. This ties back to his opening in “The Heart,” where he says, “I want to say thank you to everyone that’s been down with me; all my fans, all my beautiful fans–anyone who’s ever gave me a listen.” By the end of the song, Kendrick seems to resign himself that carrying the weight of this crown of thorns is unsustainable, repeating over and over again “I can’t please everybody.”

On “Silent Hill,” Kendrick is definitive about his desire to get away from people and all their demands. The song expounds upon the notion he alluded to in his August statement, where he said “the morning rides keep me on a hill of silence.” Apparently, his bike rides are an escape from the negativity he describes in the song. The song also features another hint at Kendrick’s infidelity, when he raps, “It’s like 6 o’clock, b*tch, you talk too much. You makin’ it awkward, love. I mean, it’s hard enough, I mean, it’s…” “Silent Hill” also features the first of many appearances by Kodak Black, the only other rapper besides Kendrick’s cousin Baby Keem (one of the many family ties), who appears on this half of the double album.

“Savior (Interlude)” opens with a passage from Eckhart Tolle, who is also featured prominently on the albums, seemingly as Kendrick’s psychological and spiritual advisor. Tolle says, “If you derive your sense of identity from being a victim–let’s say, bad things were done to you when you were a child–and you develop a sense of self that is based on the bad things that happened to you…” These words will prove to be a harbinger of things to come later on the album. From there, Baby Keem makes his first of a couple of appearances, doing the only rapping heard on the interlude. Keem reels off several unsettling details about his mother, grandmother, cousin and uncle. And, since Keem is also Kendrick’s cousin, that means these are “family ties” for Kendrick, as reinforced by the song of that title that Keem and Kendrick put out last August. Incidentally, during his verse on that song, Kendrick laid out several of the themes that would come to dominate Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers–separating himself from the public, avoiding chatter about himself, criticism of fly-by-night activism, seeking a better version of himself, being a messenger from God…It’s all there. Kendrick even mentioned Kanye West by name in the “family ties” verse, the meaning of which will come into sharper focus on “Father Time,” from The Big Steppers album. Keem’s last words on the interlude are “Mr. Morale.”

“Savior” is where Kendrick full-on removes the crown that has been foisted upon him. He starts the song by saying, “Kendrick made you think about it, but he is not your savior.” He relieves J. Cole, Future, and LeBron James of their burdens as idols, too. Kendrick bolsters the notion that he cannot be put in a box, when he raps, “like it when they pro-Black, but I’m more Kodak Black.” Perhaps, this line explains Kodak’s prominence on the album. Kodak is far from being viewed as a Hip-Hop savior. In fact, for many, he is likely viewed as the antithesis, given some of his many antics over the years. It is likely a freedom that Kendrick craves. The song also presents a radical departure from the last few. Instead of turning his tongue on his own behavior, Kendrick directs his words externally, on “Savior.” He blasts pseudo activism, calls out the contradictory behaviors around COVID vaccines while putting his own vaccination status in question (“You really wanna know?”), and chastises capitalists pretending to be compassionate. He also takes a shot at Vladimir Putin, which suggests this was one of the last songs to be recorded for the album. He closes with another reference to the benefits of his chosen life of solitude, saying he’s been “protecting his soul in the valley of silence.” He’s seemingly created a moat of silent hills and valleys for himself and his family.

J. Cole Told Dr. Dre About Kendrick Lamar & Wanted To Sign Him

“Auntie Diaries” explores how Kendrick was shaped by his earlier experiences with family ties. He details the stories of two relatives who have transitioned from female to male and male to female, respectively. He talks about his ignorant use of a slur that he thinks is harmless, until the song culminates in one of the family members drawing a parallel to Kendrick’s disapproving reaction to a white fan using the N-word when rapping along with Kendrick on stage. In one of the more revealing parts of the song, Kendrick references standing up for his trans cousin in church and says that he “chose humanity over religion.” If those words are literal, it is a significant revelation about his evolution, given how prominently religion has featured in his work from The Kendrick Lamar EP through DAMN.

Kendrick Lamar Speaks For The 1st Time About Why He Stopped A Fan From Using The N-Word

The title song of Mr. Morale is a pivotal part of the 9-song collection about Kendrick. It ties the work to The Big Steppers collection, with Kendrick directly addressing his two children. In verse 1, he speaks to his son, Enoch, telling him about his father. Being the true Gemini that he is, Kendrick explains the two, sometimes contradictory sides of himself. He’s transformed and detoxed from his past self, and yet he’s still slightly off. He’s fighting external demons, yet suggests that he has those internal demons too. He also says that he’s creative, but is afraid of the expressions that manifest. He also refers to past lives and past wives. It is important to note that Enoch was the son of Cain. In The Bible, Cain killed his brother (the first murder) and was condemned by God to a life of wandering. Thus, if Kendrick is Enoch’s father, that means he possibly sees himself as Cain.

In verse 2, Kendrick speaks to his other child, presumably his daughter, who he refers to as Uzi. If this is, in fact, her name, it would be the first time that Kendrick has mentioned it publicly. Uzis, of course, are sub-machine guns. What may be lesser known is that Uzis are from Israel, a place of obvious holy significance. So, perhaps he thinks of his daughter as a holy weapon, a reference to which he makes early in the verse (“Sharpenin’ multiple swords in the faith I believe”). Like with Enoch, Kendrick speaks in contrast to Uzi. He reflects on R. Kelly and Oprah, two people who both suffered sexual abuse as children, and notes how differently they manifested that pain. He notes the irony of serving deadly food like Popeye’s chicken at funerals. He also refers to past lives with Uzi, as he did with Enoch, saying he’s used past life regressions to better understand his traumas, perhaps work he has done with Eckhart Tolle. Kendrick also speaks of cycles that repeat in families, alluding presumably to Keem, when he says he watched his cousin struggle with addiction and then watched her watch her firstborn (Keem) make his first million, and presumably the resentment that came with that. Kendrick ends by saying he’s sacrificing himself to start the healing.

Overall, the song plays like a warning to his two children, suggesting they should deal with their traumas as they get older and not let their pain shape and define them. Their mother will give similar advice more bluntly, at the end of The Big Steppers‘ “We Cry Together.” Kendrick’s teachings to his children harken back to Tolle’s words at the top of “Savior,” and those words are bolstered at the end of “Mr. Morale,” with Tolle cautioning “People get taken over by this pain-body, because this energy field that almost has a life of its own, it needs to, periodically, feed on more unhappiness.”

“Mother | Sober” is the emotional climax of the Mr. Morale album. Like “FEAR” on DAMN, it is the song that ties several earlier references together. In verse 1, Kendrick raps about the weight of feeling that he is supposed to be a savior (“Heal everybody”). Part of that requires healing himself, and letting his ego die, a core concept of the teachings of Tolle. Kendrick references the notion of past generations following us, and trying to use material goods to assuage our pain. Kendrick raps about an incident where he heard someone in the family assaulting his mother when he was 5, and the helplessness and shame that came with his inability to help her. The experience is very similar to those Will Smith had as a child, as he witnessed his father abusing his mother. Kendrick morphed into Smith in the video for “The Heart, Pt. 5,” when he rapped the line “in the land where hurt people hurt more people,” a seeming reference to Smith’s recent public assault of Chris Rock. Kendrick also mentions transformation, a word he used on “Savior” when talking to Enoch. The word will appear multiple times in “Mother | Sober.”

Verse 2 finds Kendrick once again looking in the mirror, taking stock of himself. He talks about being asked by his family several times as a child whether his cousin molested him (was this Demetrius, who Kendrick describes in “Auntie Diaries?”). Although he denies it several times, he says the repeated inquiries sink in and cause him to question his own manhood.

In verse 3, Kendrick raps about having to address all of his traumas as a sober person. On “The Heart, Pt. 5,” he told us it was “hard to deal with the pain when you’re sober.” On “Mother | Sober,” he reveals that sex was one of his coping mechanisms. Specifically, he says it manifested in sleeping with other women while he was with Whitney. He says she asked him if he had an addiction, and he lied by saying no. It seems this may have been the set of events that ultimately led to him seeking therapy and, perhaps, guidance from Eckhart Tolle. In a line that may prove to be particularly revelatory, Kendrick says, “Whitney’s gone, by time you hear this song.” It’s unclear whether this was a temporary rift, or whether the couple has actually split.

The song ends with Kendrick addressing the unspoken sexual abuse that is widespread in Hip-Hop and the Black community (“the culture”), and exhorting that the path to freedom is forgiveness–of self and others–and that is transformation. The song concludes with Whitney congratulating him on breaking a generational curse (on Friday the 13th, no less), and his daughter thanking him, Whitney, and Enoch for doing so. Listeners of “DUCKWORTH” on DAMN may remember that this process of reversing curses started there with the actions of Kendrick’s father and Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffifth, the owner of Kendrick’s former record label. Kendrick rapped on that song—which detailed how Top was perilously close to killing Kendrick’s father before Kendrick was born—“Pay attention, that one decision changed both of they lives, one curse at a time.”

“Mirror,” Mr. Morale’s conclusion, features the return of Kodak Black. He opens the song by saying, “I choose me.” Since Kendrick has already said on “Savior” that he is like Kodak Black, we can assume Kendrick feels the same way. Given the context of “The Heart,” Kendrick’s August statement and the previous songs on Mr. Morale, the song serves as the perfect coda. Kendrick addresses the pressures he’s felt to be something he’s not, and he says he’s no longer willing to sacrifice himself for others. He suggests that if fans truly love him, their love should be unconditional, and not dependent on him being a savior. In a line that reinforces the notion that he and Whitney’s relationship may have been in jeopardy at some point, he says, “Sorry I didn’t save the world, my friend. I was too busy building mine again.” In another line that harkens back to “The Heart, Pt. 5,” he saysm “Maybe it’s time to break it off; run away from the culture and follow my heart.” Perhaps, this resolves his sentiment at the end of “The Heart,” where he says, “I want you.” “Mirror” ends with a refrain of “I choose me, I’m sorry.” It is both a concrete ending to his evolution on Mr. Morale, and perhaps serves to tee up the stories he will tell about family on The Big Steppers.

Now that we’ve completed Kendrick’s individual journey over the last 5 years, let’s turn to his evolution with his new family.

The Big Steppers

“United In Grief” serves as a summary of everything we’ve learned on Mr. Morale. From the outset, listeners are told that their fulfillment is their own responsibility. “I hope you find some peace of mind in this lifetime. I hope you find some paradise.” Whitney then tells Kendrick to tell us the truth, to which he responds that he’s been “going through something” for the last 1,855 days. In the first several lines, he lays it out, alluding to infidelity, family jealousy, repeatedly being asked about being molested, his materialism, getting therapy, and more. It works both as summary of what we’ve heard on Mr. Morale and as a primer for what’s to come on The Big Steppers, depending on how we choose to listen to the two albums.

“N95” plays like the reflection of “Savior.” Kendrick takes aim at social media posers, false prophets, capitalism, the exploitative music industry, the intrusions of fame, cancel culture, and more. The video for the song brings these themes to life. As he does on “Savior,” Kendrick makes it clear he’s giving this commentary from the safety of his own home. He tells listeners, “you’re back outside,” and later says, “venting in the safe house,” just after seemingly making his first reference to himself as “the big stepper.”

“Worldwide Steppers” introduces the whole cast of characters that makes up Kendrick’s new family of Big Steppers. Kodak Black starts by announcing Kodak Black and Oklama, both of whom we now know to be reflections of Kendrick, and Eckhart Tolle, who we now know is Kendrick’s spiritual and emotional adviser. Kendrick fills out the roster in verse 1, referencing his daughter, Enoch, and Whitney. He says of the children that when he dies, they will “make higher valleys,” presumably referring to the protections he mentioned in his August statement, and on “Silent Hill” and “Savior” on Mr. Morale. He also dives right into the problems with Whitney created by his “lust addiction,” later revealing that one of his trysts was with a white woman during his good kid, m.A.A.d. city tour. This insight into Kendrick’s world of Big Steppers also tells us he’s had writer’s block for 2 years. That and the birth of his 2 children likely explain his 5-year absence from music, yet he also tells us that the song, itself, is a result of his prayers to God for inspiration being answered.

“Die Hard” plays like a love letter to Whitney, part confessional, part seeking of affirmation, and part plea for forgiveness. Kendrick uses his own voice and those of Blxst and Amanda Reifer to articulate his feelings, with lines like “I hope you see the God in me. I hope you can see. And, if it’s up, stay down for me,” “Do you love me? Do you trust me?” and “Been waiting on your call all day. Tell me you in my corner right now.” Later, he stresses that he wants to “see the family stronger,” while acknowledging that he might still “risk it for a stranger.” This is the most we’ve ever heard from Kendrick about his years-long relationship with Whitney.

On “Father Time,” Whitney seems to give her response, starting the song with “You really need some therapy,” and telling Kendrick to “Reach out to Eckhart.” For his part, Kendrick is resistant, saying “real ni**as don’t need therapy.” What follows in Kendrick’s verses, however, plays like his confessional to Eckhart, in therapy. Kendrick recites a litany of his negative traits that stem from “daddy issues.” He talks about being toughened up on the basketball court by his father, not being allowed to be tired, feeling no pain, being taught that it wasn’t even okay to properly mourn the loss of a parent, trusting nobody, and other lessons that seem to harden his heart. Lessons from his father also seemed to burn in Kendrick’s mind that once someone crossed you they were done, as is evidenced by his line that he was confused “when Kanye got back with Drake,” the punchline to his mention of ‘Ye in his “family ties” verse (“Yeah, Kanye changed his life, but me? I’m still an old-school Gemini, lil’ b*tch“). By the end of the song, Kendrick has learned from his mistakes and those of his father, and he calls on his peers to join him in not making the same mistakes with their own kids, and treating their women partners better.

Drake Dissed Kanye West Throughout Their Concert

“Rich (Interlude)” finds Kodak Black doing the heavy lifting, as Baby Keem did on the “Savior (Interlude).” In what is more like spoken word than rapping, Kodak takes on the voice of his doubters, asking “What you doing with Kendrick? What you doing with a legend?” As Kendrick has already stated on “Savior,” Kodak knows that he and Kendrick are more similar than people may think. Kodak ends the interlude with an emphatic “Now look at this sh*t, we own property,” as if to punctuate the comparison.

On “Rich Spirit,” Kendrick opens by continuing to detail his new family life. He says, “takin’ my baby to school, then I pray for her.” Toward the end of the verse, he adds, “lil’ Man-Man [is now] the big mans.” “Man-Man” was Kendrick’s nickname as a kid, and now he is the parent dropping his daughter off at school. In the chorus, Kendrick reinforces the reclusive lifestyle he is maintaining with The Big Steppers, proclaiming himself a “rich ni**a” with a “broke phone” who is trying to keep a balance. In verse 3, Kendrick uses the same repetition of “brother” at the end of his lines as he did at the end of his verse on “family ties.” On that verse, Kendrick speaks about his life being in an amazing place and once again refers to himself as a “rich ni**a.” He also says he’s never caught cases for any crimes he might have committed. On “Rich Spirit,” during the brother passage, he insinuates that he may still do dirt, if he has to. Toward the end of the stanza in “family ties,” Kendrick says, “show my ass and take y’all to class,” perhaps making this a full-circle moment with how he began “Rich Spirit.”

“We Cry Together,” like “Mother | Sober” on Mr. Morale (also song #8), is The Big Steppers’ emotional climax. The song features Kendrick and his love interest (played by Taylour Paige, but possibly representing Whitney) having an all-out verbal slug-fest. Before the song begins, Whitney says, “This is what the world sounds like,” perhaps referring to past arguments with Kendrick, a metaphor for strife between many couples, or both. There are very specific references that fit the narratives of infidelity that have been established on the albums, but there are also details that clearly would not apply to Kendrick in real life, like them seemingly being money-strapped. The woman’s reference to 2009 suggests the argument could be a re-enactment of a past dispute, or it could be a detail to make the story feel more real. No matter the case, it is an emotional tour de force that is extremely uncomfortable to hear. It is also a completely different dimension in the expansive universe of Kendrick Lamar characters.

After exhausting their rage, the couple appears to reconcile and seems ready for makeup sex. In the outro, after sound effects of someone tap dancing, Whitney says, “Stop tap-dancing around the conversation.” Perhaps, the lesson is these types of knock-down, drag-outs are necessary to clear the emotional baggage that otherwise builds in relationships.

“We Cry Together” is intense in any context, but takes on heightened power when it is played as the second to last song in the collection, after hearing all the references to infidelity and the jabs (subtle and not so subtle) between Kendrick and Whitney throughout both Mr. Morale and The Big Steppers.

“Purple Hearts” is the coda to “We Cry Together,” and fulfills Whitney’s request of Kendrick to tell the truth on “United In Grief.” Kendrick opens his first verse with “this is my undisputed truth.” As he continues, it seems he’s learned his lessons. He raps that he would rather deny himself of other women than jeopardize his relationship: “I’d rather fast with you than f*ck it up, f*cking with skirts ’cause I’m rational.” He indicates that he’s avoiding potential traps like hanging with other rappers, engaging with social media, and going to parties. He also says other women are sorry that they are now dead to him. Toward the end of the verse, he seems to speak to Whitney, saying that he is blessed that she has an open heart, forgives, and can heal. This seems to answer the question about their current relationship status. Kendrick seems to be talking to the listeners in the last few lines of the verse. He tells us he hopes one day we can attract someone who shares our mindset and extols the virtues of being patient in life. The last words on the song, after a 3rd verse from Ghostface Killah, are a throwback to Kendrick’s new Oklama moniker. Kendrick says “if God be the source, then I am the plug talking.” Yeah, baby…

The Big Steppers seemingly concludes with Kendrick’s family intact and him embracing his role as a messenger from God. It is a hopeful ending, with Kendrick seeming to have found personal resolution about his role in both the culture and his family. Taken together, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers continues Kendrick’s tradition of making multiple bodies of work out of one release, and doing a deep-dive into the topics on his mind. In this case, the subject matter is reflecting on himself and what he brings to his family.

Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers in an incredibly complex work, both musically and lyrically. There is no doubt that this examination has only scratched the surface, and many more layers will be revealed in time. Hopefully, this framework will advance the conversation and help with Kendrick’s request on “Crown” to “keep the music in rotation.“